On Drawing

and the Dance

and the Dance

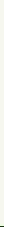

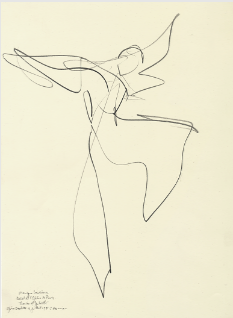

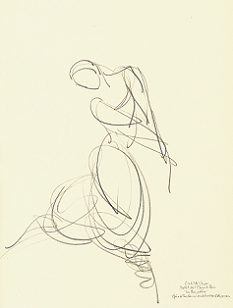

Elisabeth Maurin, 1996

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Nutcracker

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe,

Florence

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Nutcracker

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe,

Florence

''A few lines…and it is Terpsichore,

A few lines…and it is the star.

But what lines of genius!

How to praise you?

How to thank you?

Stanley!

I embrace you.''*

A few lines…and it is the star.

But what lines of genius!

How to praise you?

How to thank you?

Stanley!

I embrace you.''*

- Elisabeth Maurin

Star Dancer of the Paris Opéra

Star Dancer of the Paris Opéra

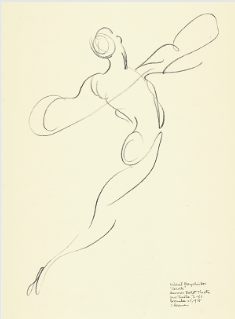

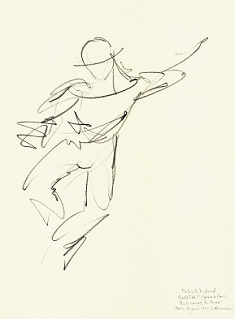

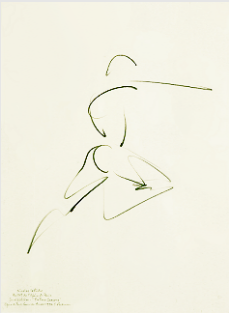

Kader Belarbi, 1996

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Four Seasons

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe,

Florence

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Four Seasons

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe,

Florence

''Stanley Roseman's draughtsmanship is a mastery of swiftly executed work with a spontaneity such as dance requires. With discipline and assurance, the sweep of his hand brings forth an economy of line, a stroke of automatism, the vitality of his draughtsmanship. His drawings are movement.''*

- Kader Belarbi

Star Dancer of the Paris Opéra"Stanley Roseman's drawings show the many facets of his great talents as a draughtsman."

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

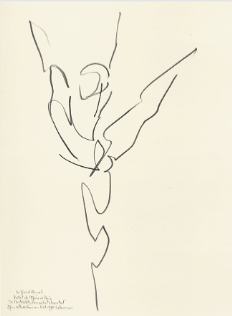

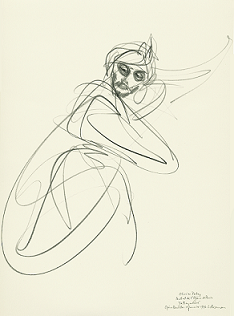

3. Mikhail Baryshnikov, 1975

American Ballet Theatre

Giselle

Pencil on paper, 35 x 27.5 cm

Albertina, Vienna

American Ballet Theatre

Giselle

Pencil on paper, 35 x 27.5 cm

Albertina, Vienna

Roseman made the Dance a subject for his drawings in New York City in the 1970's. With invitations from leading dance companies, Roseman drew at dress rehearsals and performances. The website page "Dance from New York to Paris" relates Roseman's work in New York and features drawings Rudolf Nureyev, 1975, Martha Graham Dance Company, collection of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem; and Mikhail Baryshnikov, 1975, American Ballet Theatre, collection of the Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, also presented below, (fig. 3).

The Dance holds an important place in Roseman's oeuvre. With a passion for drawing and a love for the dance, Roseman states: "I felt the dancer's language in harmony with my own as a draughtsman.''[1]

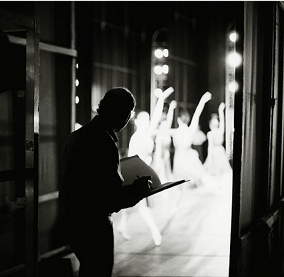

4. Stanley Roseman drawing from the wings of the stage of the Paris Opéra.

Roseman was invited in 1989 to draw the dance at the illustrious Paris Opéra. The prestigious invitation from the administration of the Paris Opéra was greatly meaningful as the Dance holds a preeminent place in the cultural tradition in France and is an important subject in French art.

The Bibliothèque Nationale de France states that Roseman's work on the dance "gives an answer to the challenge of expressing movement in a single pictorial image.''

The superb drawing Mikhail Baryshnikov depicts the celebrated dancer as Duke Albrecht in the American Ballet Theatre's production of Giselle. The great Romantic ballet, with haunting scenario by Théophile Gautier and beautiful score by Adolphe Adam, was commissioned by the Paris Opéra and had its world premiere at the opera house in 1841.

The drawing of Mikhail Baryshnikov is atypical of the frontal position in which dancers are usually depicted in art. Baryshnikov is seen here moving upstage in a curvilinear composition that focuses on the turn of the dancer's head and outstretched arms beneath voluminous sleeves. With a minimum of line, Roseman creates a splendid abstraction of the male dancer in flight.

"My interest in the dance is neither to illustrate the story of a ballet nor to depict dancers in repose or readying for a performance. For me the subject of the dance is the dancer dancing. Stimulated by the athleticism and sensuality of the dance, I am interested in the dancer's emotive use of movement as a means of personal expression."

Drawing - The Foundation of the Visual Arts

At the Paris Opéra

Drawings account for a great part of Roseman's oeuvre. Speaking about the importance of drawing, Roseman cites Giorgio Vasari, the celebrated sixteenth-century Florentine architect, painter, and biographer of Lives of the Artists, who writes that drawing is ''the parent of our three arts, Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting, having its origin in the intellect.''[3] Roseman also pays homage to Leonardo da Vinci:

''That drawing is considered the foundation of the visual arts nurtured my early convictions as to the importance of drawing and the time spent in my work as a draughtsman. For Vasari, drawing was the animating principle of the creative process. Leonardo da Vinci said that drawing is 'indispensable' to the painter, sculptor, and architect, as well as the potter, weaver, embroiderer, and goldsmith. It was drawing, Leonardo affirmed, that gave the writer his alphabet, the mathematician his figures, and taught geometers, astronomers, machine builders, and engineers.[4] However, the translation of the Italian word disegno as 'drawing' limits the meaning of the word, for the Florentine Renaissance concept of disegno encompassed more than just a method for recording. Disegno embraced a way of seeing and thinking.''[5]

The Musée Ingres, Montauban, houses an outstanding collection that grew from an important bequest by its native son Ingres. The bequest includes a large corpus of drawings in graphite pencil, a medium preferred by the French master. The Museum conserves a suite of Roseman's drawings on the dance, including Charles Jude and Michaël Denard, 1991, from José Limon's The Moor's Pavane, a balletic version of Shakespeare's Othello. (See "Biography,'' Page 2 - "Variety of Drawing Materials and the World of Shakespeare.'')

Presented here is Olivier Patey, 1996, an impressive drawing of the premier dancer as the Rajah in Rudolf Nureyev's last choreography La Bayadère, set in a past century in India, with a memorable score by Ludwig Minkus, (fig. 5).

5. Olivier Patey, 1996

Paris Opéra Ballet

La Bayadère

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

Paris Opéra Ballet

La Bayadère

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

Roseman renders the dancer in dramatic contrapposto. Flowing, curvilinear lines convey the movement of the voluminous robe and sleeves of the turbaned Rajah, who, with deep set eyes and closely cropped beard, glances over his shoulder as he advances forward across the spacial dimension of the paper.

"I thank you and want to express my conviction that the artist is

an outstanding draughtsman and painter

to whom much recognition and success are due."

an outstanding draughtsman and painter

to whom much recognition and success are due."

- Dr. Walter Koschatzky

Director of the Albertina

Director of the Albertina

Dr. Walter Koschatzky, Director of the Albertina, writes in a cordial letter, dated 1978, to Ronald Davis, who introduced Roseman's work to the Museum:

- Stanley Roseman

6. Clotilde Vayer, 1992

Paris Opéra Ballet

La Bayadère

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Musée d'Art Moderne et Contemporain,

Strasbourg

Paris Opéra Ballet

La Bayadère

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Musée d'Art Moderne et Contemporain,

Strasbourg

The eminent Curator of Patrimony and Director of the Museums of Strasbourg Rodolphe Rapetti, who was later appointed Chief Curator of Patrimony and Deputy Director of the Museums of France; and the respected Curator of the Cabinet of Prints and Drawings of Strasbourg, Anny-Claire Haus, write in a gracious letter of 1996 to Ronald Davis:

- Rodolphe Rapetti

Curator of Patrimony and Director

Museums of Strasbourg

Curator of Patrimony and Director

Museums of Strasbourg

- Anny-Claire Haus

Curator, Cabinet of Prints and Drawings

Museums of Strasbourg

Curator, Cabinet of Prints and Drawings

Museums of Strasbourg

"A work that is really very beautiful. . . ."

- Georges Vigne

Curator, Musée Ingres

Curator, Musée Ingres

In a cordial letter of appreciation to Ronald Davis, the Curator and Ingres scholar Georges Vigne praises the drawing of Olivier Patey in La Bayadère as:

Although drawings have traditionally served as studies or drafts for compositions to be realized in other mediums, drawings can be independent works of art, as are Roseman's drawings on the dance.

"Drawing is the integrity of art.''

The French master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) asserts by his well-quoted maxim: "Drawing is the integrity of art.'' The Ingres scholar Agnes Mongan, in her Introduction in the Harvard University catalogue to the drawing exhibition Ingres - Centennial Exhibition 1867-1967, cites the influence that Ingres had on following generations of artists: "Degas, for example, who worshipped him and collected his work; Renoir, who watched quietly from a distance with fascinated admiration as Ingres made quick drawings in the Bibliothèque Nationale . . . and Picasso, who has turned to Ingres again and again . . . .''[6] As Roseman notes in his journal: "I find it especially interesting that the three artists mentioned by Professor Mongan in reference to Ingres and drawing: Degas, Renoir, and Picasso - as well as Ingres himself - dedicated imagery to the subject of dancers.''

Drawing from Life

In the fine art book, Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, (Paris, 1996), the artist writes in his text "On Drawing and the Dance'' of his working methods and thoughts on art. "The presence of the model is a generative force to the creation of my work. That is one of the reasons I do not work from photographs or rely on the camera's translation of form and space onto the two-dimensional surface.'' Roseman's understanding of the dance and his ability to capture dance movements on paper coincide with his interest "in the perception of movement and the expression of that visual experience in a single pictorial image.''[7]

The eloquent drawing presented here, (fig. 6), depicts premiere danseuse Clotilde Vayer as Nikiya in La Bayadère, the fateful love story of an Indian temple dancer, or bayadère, and the noble Indian warrior Solor.

Drawing with a Graphite Pencil

Roseman delineates the dancer's head, uplifted arms, broad chest, and tapering abdomen ''with a few masterful strokes of a pencil'' (Associated Press, Paris). A single, continuous, undulating line defines the dancer's lower torso and muscular legs: the right leg, a pillar of support; the left leg thrust high into the air. In this dynamic composition Roseman creates an electrifying image of the male dancer.

The Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, houses a celebrated collection of master drawings, notably from the Italian Renaissance, as well as from the French, Flemish, German, and Dutch schools. The Museum acquired in 1996 a suite of Roseman drawings on the dance at the Paris Opéra. The superb drawing reproduced here, (fig. 7), depicts Paris Opéra star dancer Wilfried Romoli in the exciting, modern dance piece In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated, choreographed by William Forsythe for the Paris Opéra Ballet to Tom Willems' pulsating score for synthesizer.

Barbara Brejon de Lavergnée, distinguished Curator of the Cabinet of Prints and Drawings of the Lille Museum, writes warmly in appreciation to Ronald Davis, who introduced his colleague's work to the Museum:

''The drawings that you so thoughtfully brought to us are superb. I love immensely the drawings of the dancers, which have an astonishing spontaneity of action and of refinement. . . .

''Please convey my congratulations to Monsieur Stanley Roseman for the great quality of his drawings. We are proud to incorporate the work in our collection."

- Barbara Brejon de Lavergnée

Curator of the Cabinet of Prints and Drawings

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille

Curator of the Cabinet of Prints and Drawings

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille

7. Wilfried Romoli, 1993

Paris Opéra Ballet

In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille

Paris Opéra Ballet

In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille

On Drawing and the Dance

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

''You have presented the Cabinet of Prints and Drawings of the Museums of Strasbourg with an ensemble of five drawings of great quality by Stanley Roseman. . . . These remarkable portrayals of dancers of the Paris Opéra Ballet and of an actress drawn at the Ranelagh Theatre integrate quite naturally in the suite of our prestigious series of works by Bakst and Rodin and enrich in a wonderful way the collection of the Cabinet of Prints and Drawings."

8. Monique Loudières, 1995

Paris Opéra Ballet

Romeo and Juliet

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

British Museum, London

Paris Opéra Ballet

Romeo and Juliet

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

British Museum, London

Presented here is Roseman's magnificent drawing Monique Loudières, 1995, in the British Museum, London, (fig. 8).

With a brilliant use of line, the artist has captured on paper the star dancer at a climactic moment in the ballet when Juliet rushes into the crowd of feuding Capulets and Montagues to discover the body of her cousin Tybalt, who has been killed in a fierce duel with Juliet's beloved Romeo.

The Bibliothèque Nationale de France in its exhibition publication Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris, (1996), notes that Roseman had become " 'an honorary member' of the ballet troupe.''[2] The artist drew at rehearsals in the dance studios and at the pré-générale and répétition générale (dress and final dress rehearsals) in the auditorium. Roseman was given the extraordinary privilege to draw from the wings of the stage of the Paris Opéra on opening nights and at subsequent performances during seasons of ballet and modern dance.

© Stanley Roseman

Roseman's continuous pencil line - like a flash of lightning - is charged with emotion and expresses at once the outward kinetic movements of the danseuse and the inner turmoil of Juliet as she thrashes with conflicting feelings of family loyalty to her cousin and devotion to her lover.

The Musée d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Strasbourg, conserves an excellent suite of Roseman's drawings that includes the present work. The Museum's collection includes drawings by Bakst for the Ballets Russes and drawings by Rodin of Isadora Duncan, who danced in Paris in the early twentieth century.

© Stanley Roseman

The Paris Opéra Ballet presented in 1991 Push Comes to Shove by Twyla Tharp. This signature work of the American choreographer integrates elements of modern dance and jazz with classical ballet. Paris Opéra star dancer Patrick Dupond premiered the work at the Paris Opéra in 1991 and is seen here in the marvelous drawing in the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, (fig. 9).

With an exciting interaction of fluent, zigzag, and syncopated lines, Roseman captures on paper the exuberance of Patrick Dupond dancing to the ragtime music of Joseph Lambs' Bohemia Rag.

Two swift, parallel strokes of the graphite pencil define the low neckline of the dancer's shirt and the brim of his bowler hat. Light lines evolve into strong, dark strokes and seem to dissolve into gray filaments.

The diagonal composition with the thrust of the male dancer's torso, legs bent at the knees, and left arm raised and pushing back accentuates the forward movement of the figure dancing across the picture plane.

9. Patrick Dupond, 1991

Paris Opéra Ballet

Push comes to Shove

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Paris Opéra Ballet

Push comes to Shove

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

© Stanley Roseman

Roseman's fluent, pencil lines in ribbon-like arabesques express the graceful balletic movement of Clotilde Vayer, her head inclined and arms extended forward as she turns to the side. In this engaging work the artist beautifully conveys the femininity and emotion that the danseuse in the role of Nikiya projects to the viewer.

Monique Loudières brought a passionate interpretation to the role of the tragic heroine, a role that the celebrated ballerina reprised over the years at the Paris Opéra as well as abroad, always to great acclaim.

Tchaikovsky's third and last ballet The Nutcracker premiered at the Maryinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, in 1892. This enchanting ballet tells the story of a young girl Clara who receives from her godfather on Christmas Eve a present of a nutcracker in the form of a soldier. That night Clara dreams the toy soldier transforms into a handsome prince who escorts her into a fantastic world where even snowflakes waltz to beautiful music.

11. Nicolas Le Riche, 1996

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Four Seasons

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe,

Florence

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Four Seasons

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe,

Florence

12. Kader Belarbi, 1996

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Four Seasons

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Four Seasons

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence

- Stanley Roseman

10. Elisabeth Maurin, 1996

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Nutcracker

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe,

Florence

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Nutcracker

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe,

Florence

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

From his early career Roseman pursued subjects that took him from the artist's studio into the environments of his models, such as dance studios and the wings of the stage of the Paris Opéra. "While unfamiliar environments meant adjusting to new working spaces and conditions of light and often much activity around me, I ultimately found such circumstances conducive to my own creative process.'' The artist further relates in his text: "At performances I drew from the wings. It was exciting to create my work in proximity to the dancers on stage."[9]

Roseman recounts: "From the time I began drawing the dance at the Paris Opéra in 1989, I had hoped the Company would reprise The Nutcracker with Nureyev's choreography and Elisabeth Maurin as Clara. I did have the wonderful opportunity to draw Elisabeth in the role in which this great ballerina was promoted to étoile (star dancer) in 1988 by Nureyev, then Director of the Dance. It had been eight years since Nureyev's The Nutcracker was presented at the Opéra, and Elisabeth's appearance in the ballet was very much anticipated by the Company, by the ballet-going public, and by me.

The Uffizi Gallery, which houses a world-renowned collection of master drawings, acquired the above work Elisabeth Maurin with three equally superb Roseman drawings on the dance at the Paris Opéra. The document of acquisition enumerates ''four drawings by Stanley Roseman inspired by the dance'' and states that the works ''will enrich the collection of the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi."

The Museum's acquisition of Roseman's drawings include Charles Jude and Florence Clerc, 1991, presented on the home page and "On Drawing on the Dance," Page 4 - "Pas de Deux;" Nicolas Le Riche, 1996, (fig. 11); and Kader Belarbi, 1996, (fig. 12), presented below.

For the gala reopening of the Paris Opéra, Palais Garnier, in March 1996, after a year and a half of renovation, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France presented at the Bibliothèque-Musée de l'Opéra, housed in the Palais Garnier, the exhibition Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris, which spanned six years of the artist's work at the Opéra. Jean Favier, President of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, opened the exhibition on March 12 and signed the exhibition guest book: "avec ma très sincère admiration."

Paris Opéra star dancer Monique Loudières danced the role of Juliet at the Paris Opéra premiere in 1988 of Rudolf Nureyev's balletic version of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. The symphonic ballet score, in four acts, deeply expressive of Shakespeare's epic tragedy, was composed by Serge Prokofiev in 1935.

Photo © Ronald Davis

In his text "On drawing and the Dance,'' Roseman states that a primary concern for him in expressing a subject or theme in his drawings is his choice of materials "because of the characteristics inherent in each medium." For his drawings on the dance he employs a graphite pencil. Roseman concludes his discourse on the use of pencil for drawing the dance: ''Pencil is a drawing instrument by which I could explore an extensive range to the quality of the line, not only to express the human form in changing patterns of dance movements but also to carry and transmit in a graphic medium the kinetic energy of the dancer.''[8]

Roseman recounts in his journal: "At the outset of my work at the Paris Opéra in 1989, when I was invited to draw in the dance studios, I was, of course, an unfamiliar presence in that private environment of working rehearsals. Now I was part of that familial environment, and with the upcoming openings of my exhibition on March 12 and the Paris Opéra Ballet on March 18, I was especially looking forward to drawing the dancers in The Four Seasons."

"I was always very happy to draw Nicolas Le Riche and Kader Belarbi, who gave me much inspiration for my work over the years," recounts Roseman. "Their virtuoso dancing in ballets and works of modern dance was greatly acclaimed. I deeply appreciated their enthusiasm for my drawings on the dance.''

Nicolas Le Riche and Kader Belarbi, knowing from Roseman of his intention to include drawings from The Four Seasons in the exhibition, "danced in rehearsal with all the energy and emotion of a performance," recounts the artist in gratitude to the star dancers.

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

With a few, swift, sure lines of a graphite pencil, Roseman expresses the force of Nature conveyed by Nicolas Le Riche seen here in the dance segment "Autumn." Bold strokes define the taut musculature of the shoulder, back, and buttocks of the male dancer bounding across the picture plane in this dynamic composition drawn with "perfectionism and spontaneity, qualities that are prized by the dancer,'' writes Nicolas Le Riche of Roseman's work.[10]

"The rehearsal halls and wings of the Paris Opéra were my studio, and many of the greatest dancers today were the subjects of my drawings. Even with the familiarity of repeated rehearsals and performances, I could not contain the excitement I felt each time I resumed my work. I was inspired by the music and the dance to draw.''

The exhibition included the two splendid drawings of Paris Opéra star dancers Nicolas Le Riche and Kader Belarbi in The Four Seasons, (figs. 11, 12).

In preparation for the exhibition, Roseman drew at rehearsals of The Four Seasons to include drawings from the Paris Opéra Ballet program that was to open at the Palais Garnier on March 18. The program concluded with the Paris Opéra premiere of The Four Seasons choreographed by Jerome Robbins to the effervescent ballet music by Giuseppe Verdi from his opera I Vespri Siciliani, with additional music from the composer's Jerusalem and Il Trovatore. I Vespri Siciliani was commissioned for the Paris Opéra, where it premiered in 1855.

In joyful celebration of Spring, Kader Belarbi, seen here, strides forward, arms outstretched and head inclined, in a lyrically expressed dance movement that the artist skillfully conveys with pencil and paper. Kader Belarbi writes of Roseman's work: ". . . the sweep of his hand brings forth an economy of line, a stroke of automatism, the vitality of his draughtsmanship. His drawings are movement."[11]

The Uffizi, Florence, conserves the present work Elisabeth Maurin, (fig. 10), a sublime drawing of the star dancer in her acclaimed role as the dreamy young Clara in The Nutcracker. Roseman eloquently conveys with a purity of nuanced line the gracefulness, tenderness of emotion, and virtuosity of Elisabeth Maurin dancing to an exquisite musical passage with silvery tones of a celesta, the instrument Tchaikovsky introduced in this beloved score.

"The Nutcracker was the first ballet I attended when I was a boy growing up in New York. The memory of that wonderful experience in a distant holiday season filled me with emotion on Christmas Eve in Paris in 1996 as I stood in the wings of the stage of the Paris Opéra and drew Elisabeth Maurin dancing to Tchaikovsky's marvelous music."

ON DRAWING AND THE DANCE Continued

* Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris, (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996), pp. 12, 13.

1. Stanley Roseman, Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, (Paris: Ronald Davis, 1996), p. 9.

2. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris, (text in French and English), p. 11.

3. Giorgio Vasari, Vasari on Technique, (New York: Dover, 1960), p. 205.

4. Serge Bramly, Leonardo, (London : Michael Joseph, 1992), p. 260.

5. Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, p. 9.

6. Agnes Mongan, Ingres - Centennial Exhibition 1867-1967, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University, 1967), p. xvii.

7., 8., and 9. Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, p. 14.

10. and 11. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris, (text in French and English), pp. 13, 14.

1. Stanley Roseman, Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, (Paris: Ronald Davis, 1996), p. 9.

2. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris, (text in French and English), p. 11.

3. Giorgio Vasari, Vasari on Technique, (New York: Dover, 1960), p. 205.

4. Serge Bramly, Leonardo, (London : Michael Joseph, 1992), p. 260.

5. Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, p. 9.

6. Agnes Mongan, Ingres - Centennial Exhibition 1867-1967, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University, 1967), p. xvii.

7., 8., and 9. Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, p. 14.

10. and 11. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris, (text in French and English), pp. 13, 14.